On February 28, 1928 Colleen Moore signed what was going to be her last contract with First National. Moore had been the company’s prime money maker since her big break in Flaming Youth back in 1923. Her previous contract had included four films made 1927-28, Her Wild Oat, Happiness Ahead, Oh Kay, and the blockbuster Lilac Time.

The Swedish poster for Lilac Time

Early 1928 Colleen Moore was in a very good position to renegotiate her contract. One could say that the contract she was to sign was quite favorable. It stipulated that Colleen was to have final say over scripts, continuity, directors, photographers, male leads and cutting. She was obliged to make four photoplays and receive $150,000 per film. This made her just about the best paid actress in Hollywood at the time. Her husband and producer John McCormick who also was included in her contract didn’t believe in the coming of talking pictures so there was no mention of any singing or talking in the contract. One must also keep in mind that in February of 1928 talking pictures were just The Jazz Singer and some vaudeville shorts, nothing else.

The first film to be produced within her new contract was Synthetic Sin, a script which she approved of in March 1928. The script itself had been under development for over six months and Colleen was eager to shoot it. She still had to finish work on the last two films in the old contract first, Happiness Ahead and the silent version of the Gershwin musical Oh Kay. Both were made during spring 1928 and opened in May and August respectively. Lilac Time was already finished and waited for the fall season with an August premiere and a general release in October. With its enormous sets and multitude of extras, Lilac Time had cost more than the other three films together, so it was crucial it became a hit. By the end of its lengthy run it turned out to become the second most grossing film during the 1920’s. The biggest money maker until 1939 was The Singing Fool which coincidentally went up side by side with Lilac Time in the fall season of 1928.

Work on Synthetic Sin started in September ’28 but the other three films in the new contract were not yet decided. Normally the studio had a fair amount of forward planning, and when a four picture deal was settled it was often known which films were to be produced. Scripts were usually approved and directors appointed well in advance. Sometimes things didn't run as smoothly. McCormick had a script called The Richest Girl in The World which he thought suitable as Colleen’s next offering. William A. Seiter was to direct it. Even a starting date for it was set to November 5th.

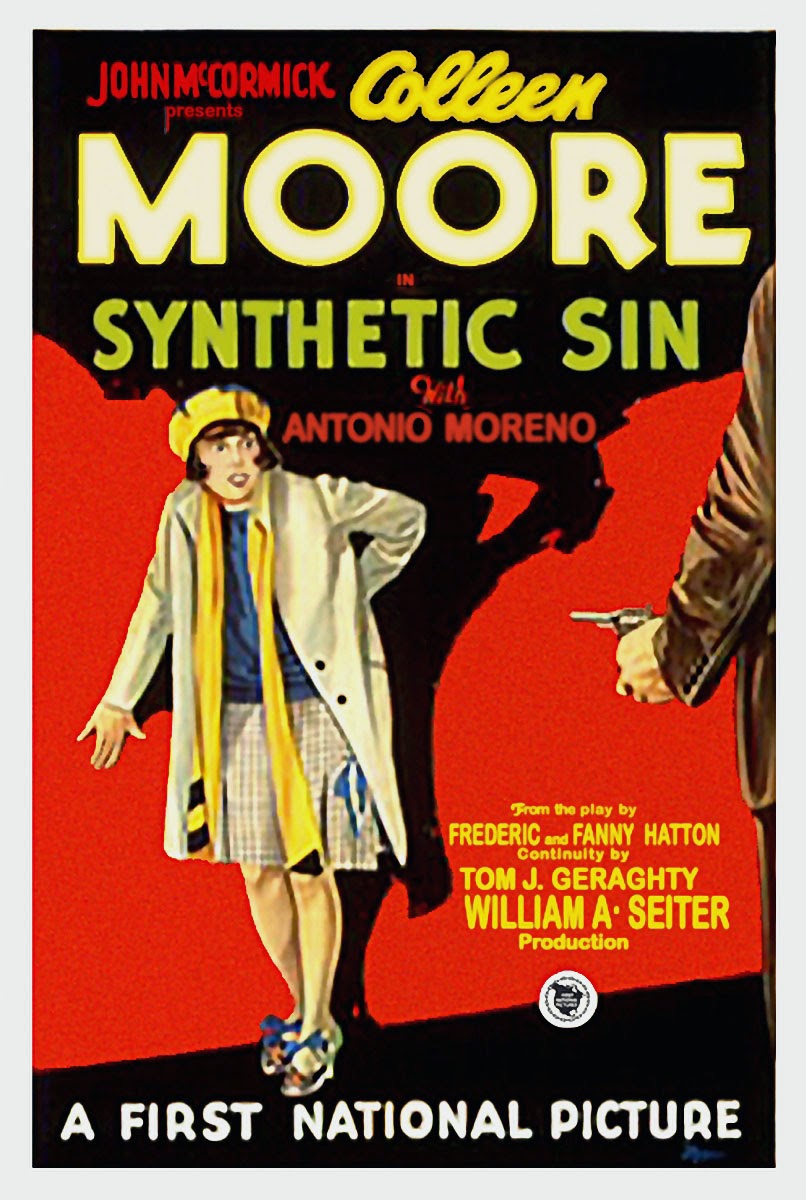

Colleen Moore in Synthetic Sin

Hollywood movie making was quickly changing and with the thundering success of Warner’s second talkie, The Singing Fool in late September 1928, the other studios quickly had to reconsider their shooting schedules. First National decided that it would be favorable if Colleen agreed to do a talking picture since that was the new thing everyone was talking about. Colleen was the biggest star of the studio but her contract also granted her complete control and the possibility to refuse to talk on film if she felt like it, she had at least no contractual obligation to comply with this request. The studio cancelled The Richest Girl In The World because the script wasn't sufficiently developed (it was later revised into a 1934 Miriam Hopkins talkie, still with William A. Seiter directing it). First National suggested several titles to replace it, including When Irish Eyes Are Smiling, Funny Face and Dangerous Nan McGrew, and it had to be a talkie. That was if Colleen would agree to renegotiate her contract.

In October 1928 Warner Brothers bought two thirds of First National and since Warner’s was the leading studio of the talkie craze the demand to release talking pictures grew day by day. Before renegotiating Colleen’s contract the studio wanted to make sure she had a voice. She recited the nursery rhyme Little Bo Peep as her voice test. Colleen’s voice recorded just fine and was indeed considered suitable for talkies. However, she still had to go to a voice coach and even take singing lessons like everyone else who wanted to be a star of talking pictures. The coming of talkies was clearly a way of the studios to clean out all sorts of disadvantages and put pressure on their stars.

By this time Synthetic Sin was almost finished and a script for a second silent comedy was quickly decided, probably to buy some time to prepare for Colleen’s first talkie. The script was initially called That’s A Bad Girl but the studio finally settled on Why Be Good as the title. Mid November, just as shooting of Synthetic Sin wrapped, Colleen and McCormick took a week off and went through the heaps of suggested scripts to find the next film, Colleen’s first talkie. The choice fell on When Irish Eyes Are Smiling later renamed Smiling Irish Eyes, but it needed a lot of work to be turned into a working talking picture. Well home again, work on Why Be Good started immediately. With the success of MGM’s Our Dancing Daughters that had been running since September, First National wanted a similar vehicle to cash in on the youthful shopgirl movie fad.

In January 1929 Colleen agreed to renegotiate her contract with First National. The revision consisted in that the final two films left on her February 1928 contract were to be all-talking. She would get an additional $25.000 for each talking picture which meant she would get $175.000 per movie. McCormick who still was included in his wife’s contract was to get $35.000 per movie, a raise with $2.500. The contract more or less settled that the last silent picture Colleen was to appear in was Why Be Good.

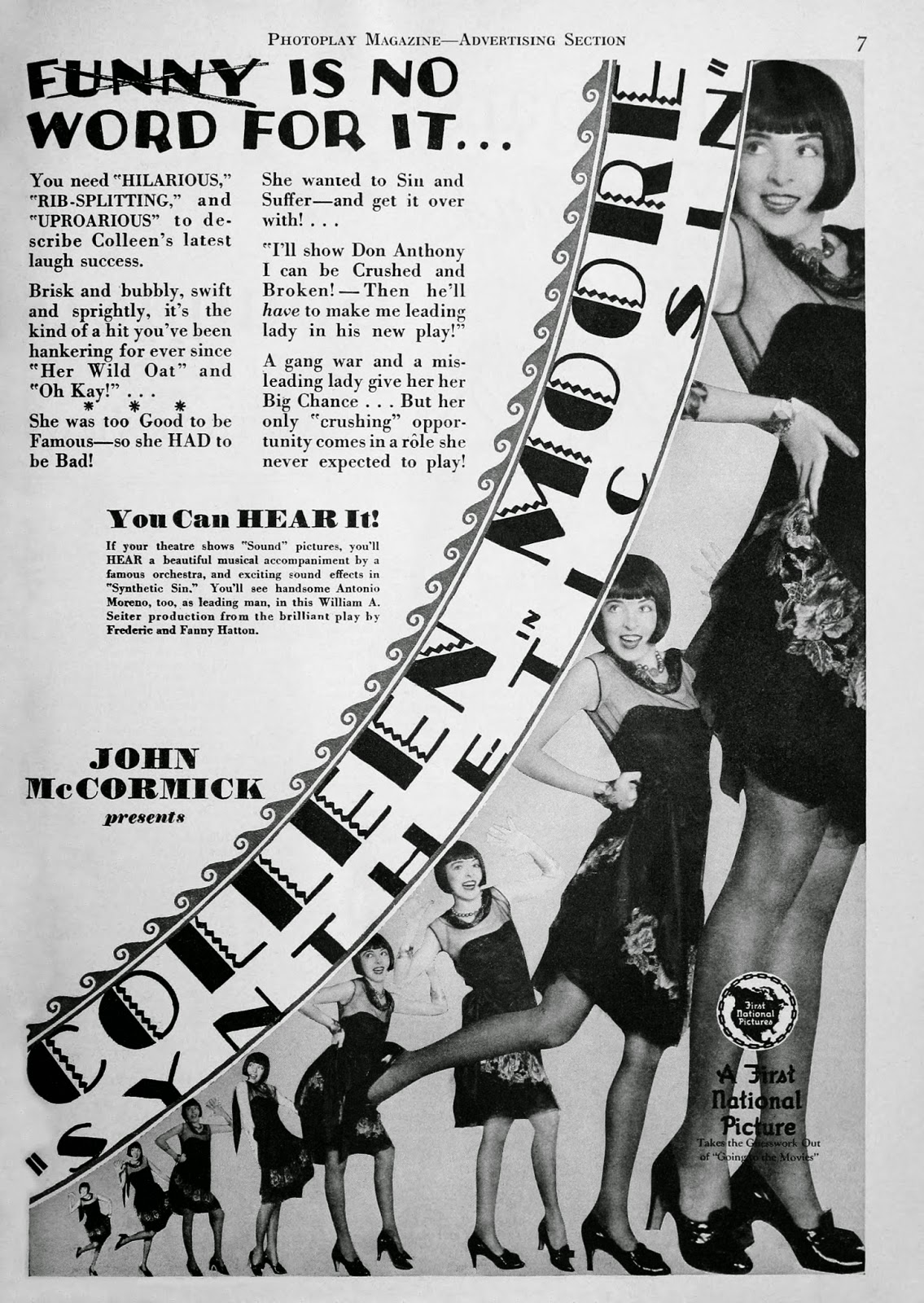

Magazine ads for Synthetic Sin and Why Be Good (1929)

Synthetic Sin opened January 6th 1929 but wasn't a big success according to period reviews. However it wasn't exactly a bomb either as the public quite liked it, even more so with Why Be Good that opened two months later. It was clearly considered the better of the two. Why Be Good was basically an updated remake of Flaming Youth and was marketed as such. The press called it “peppy and entertaining”. None of the two films were seen as remarkable or outstanding by any sense, just typical Colleen Moore comedies.

Synthetic Sin and Why Be Good were shot almost back to back late autumn 1928, both had a synchronized score and sound effects but no dialogue. They were no high budget melodramas but quickly produced rapid paced comedies. Like so many other of Colleen’s comedies they were directed by William A.Seiter. As silent pictures quickly were falling out of fashion, the fan magazines and the press in general mostly neglected this type of movies in favor of bigger productions and all talking extravaganzas. We should be grateful that these two films have survived at all. Both actually did very well at the box office, each earning more than $750,000 against an initial cost of about $325,000, which was outstanding for silents in 1929, especially considering not very favorable reviews.

At the time when Why Be Good was released there were rumors running that Colleen would make one talkie and then end her career. This may very well have been her initial thought but to fulfill her contract she had to make two talkies before she could bow out. Smiling Irish Eyes and Footlights and Fools, shot during the spring and very hot summer of 1929. Both were lavish all-talking productions that included big production numbers and several Technicolor sequences. Sadly neither of the two survives to our time. Colleen was not at all pleased with how she turned out in them. She later said that especially Smiling Irish Eyes was a frightfully dull film and she wasn't surprised it flopped. Looking back this may explain why both her 1929 talkies were unsuccessful. She was clearly uncomfortable with the new way of making movies even though she had a voice. After fulfilling the contract Colleen took a break from movie making concentrating on dollhouses, successful investments and personal matters. Her days as a movie star were over.

Colleen divorced John McCormick in 1930. She returned to the screen briefly in 1933 and made four films for four different studios of which the first film, The Power And The Glory (Fox) is the one she liked best according to her memoirs Silent Star (1968).

The Restoration

Until the late 1990s both Synthetic Sin and Why Be Good were thought to be lost. There is an extremely high mortality rate for films released during the 1927-29 transition period. A large fire at Warner Brothers in the 1950's destroyed the then-known prints.

Fast forward to 2002 and New York's Film Forum. Prior to a screening, Ron Hutchinson of The Vitaphone Project updated the audience on the project’s latest activities. He casually mentioned that he recently acquired all the soundtrack disks for Colleen Moore's Why Be Good , and said something to the effect that "unfortunately, this is a lost film."

Film historian Joe Yranski, who ran the film library at the Donnell Media Center, had been a longtime friend of Colleen Moore's and knew more about this film than probably anybody on the planet, yelled out "No it's not! I know where it is!" The full house at Film Forum cheered.

Ron Hutchinson of The Vitaphone Project

Ned Price, Warner Brothers Chief Preservation Officer and the driving force behind the studio’s support of nearly 150 Vitaphone short restorations, personally interceded with the Cineteca di Bologna and negotiated a mutually agreeable arrangement to have both films restored and copies of both finished efforts given to the archive.

Work began late in 2012, with the professional transfer of Ron’s Why Be Good disks and the lone disk for Synthetic Sin by sound engineer Seth Winner. The restoration effort represents a true partnership between Warner Brothers, UCLA Film and Television Archive, Joe Yranski, and The Vitaphone Project, and was completed in June 2014.

Synthetic Sin and Why Be Good were recently screened, for the first time in over 80 years, in 35mm and sound. The 2014 screenings in Bologna, Pordenone, London, Los Angeles, Chicago and New York were all literally packed to the last seat. One could assume that Colleen Moore's fanbase is growing with these discoveries.

Seen today both films are definitely well budgeted, have strong First National art direction with a heavy art deco slant. In the case of Why Be Good, there is the added attraction of Jean Harlow as a prominent dress extra (seen making out with a guy on a couch), and a super musical score with top jazz musicians of the period.

Jean Harlow as a dress extra on a couch

Why Be Good is available on DVD from Warner Archive. Be sure to get a copy of it.

The preservation state of the movies discussed above:

Her Wild Oat (1927) - Survives complete

Happiness Ahead (1928) - Lost

Oh Kay! (1928)- Lost

Lilac Time (1928) – Survives complete

Synthetic Sin (1929) – Survives with sound fragment

Why Be Good (1929) – Survives complete

Smiling Irish Eyes (1929) – Lost, sound survives

Footlights And Fools (1929) - Lost, sound survives