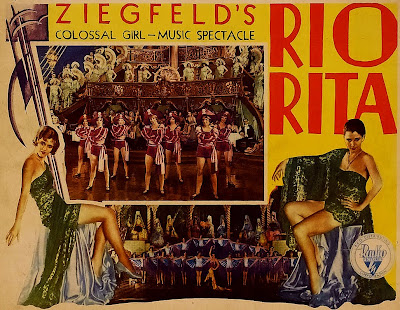

Original promotional material published in Film Daily in July 1929

The other day I got a mail from my friend Brian who told me about a sensational find he had made on You Tube. Someone had decided to upload two fragments from the supposedly lost 1929 version of Rio Rita. To me this is a sensation! Judging from the number of showings it has, not many people have found it yet. There is almost no information about it other than the uploader says the footage comes from a reel of film he found in an estate sale a while ago.

The two snippets Mr McClutching has posted are indeed from the original 1929 version of Rio Rita. The footage is not present in the 1932 re-release version that is in circulation today. The snippets seems to be filmed straight off a screen or a wall but look fantastic nevertheless. The film elements appears to be in almost perfect condition considering its age. The color depth looks amazing, almost too good to be true. Let's take a look at it!

The first snippet comes from the beginning of the movie where Dorothy Lee is introduced with a little number called The Kinkajou. As I understand this was the first musical number in the movie. It has been entirely removed in the 1932 version.

The second clip is a fragment from the latter half of the Sweetheart We Need Each Other reprise aboard the pirate barge. This clip comes from the massive color segment towards the end of the movie.

The beginning of the number and more information about the cut/uncut version of Rio Rita can be found in my previous post about cut musical numbers.

Watching these resurfaced fragments it becomes somewhat easier to understand why this footage was cut in the 1932 version. The most obvious reason was of course the running time. A 105 minute move was (and is) an easier sell than a 140 minute movie. But which scenes could be cut without crippling the plot too much? The easiest way was of course to cut songs as they usually don't move the plot forward. But this must have been difficult since Rio Rita was an operetta. Why was the peppy Kinkajou song cut and other slower songs saved? The Kinkajou was after all a major hit and one of the better known songs from the 1927 Broadway show. My guess is that it has something to do with the performance.

Here's a Ampico piano roll of The Kinkajou published in 1927, recorded by Ferde Grofé

In 1929 talkie musicals were something completely new. Methods of cinematography and sound engineering had not found their final form. The crew that made Rio Rita were pioneers in many ways. They had no recipe, they had to improvise.

In 1932 however the movie musical stood before its second coming. Almost every aspect in moviemaking had evolved incredibly fast during the three years between the two versions. What was groundbreaking in 1929 was not even yesterdays news in 1932.

My guess is that most of the cut material in Rio Rita was considered old-fashioned. Let's face it, Dorothy Lee was adorable in almost every way, but her rendition of The Kinkajou seems a bit clunky and the choreography isn't exactly top notch. The staginess of parading chorus girls walking up and down stairs in the second fragment is very 1929 but had no place in 1932. The 1932 audience was experienced and probably found Rio Rita quite dull even after it had been "modernized". Let's hope these fragments ends up in a complete 1929 version soon. Until then, it feels great knowing they exist and appears to be in great shape.

The 1929 trailer for Rio Rita

A personal favorite I have mentioned many times on this blog.

A personal favorite I have mentioned many times on this blog. .jpg)